Exhibition Overview

As one of the most talented and innovative artists of the twentieth century, Park Rehyun (1920–1976) transformed the entire field of Korean ink-wash painting by freely crossing the boundaries of ink-wash, printmaking, and tapestries. But following her untimely death from cancer, her art was gradually forgotten, until she was primarily remembered as the wife of Kim Kichang.

At a time when few Korean women could sustain a career as artists, Park Rehyun had to strive constantly to juggle her artistic production with her demanding life as a mother and the wife of a hearing-impaired husband. By incorporating domestic handicrafts and motifs from her daily routines into her works, she expanded the modes of artistic expression and achieved her own independent vision based on her identity as a mother, woman, and Asian.

This exhibition introduces the life and art of Park Rehyun, who overcame social restrictions on women while still embracing her domestic responsibilities. Both as a loving wife who mastered English, Korean, and lip-reading in order to help her husband communicate and as a pioneering artist who excelled in painting, tapestry, and printmaking, Park Rehyun was indeed a “triple interpreter.”

I. Modernism in Korean Ink-wash Painting

Born and raised in the colonial period, Park Rehyun went to Japan to study modern Japanese ink-wash painting. Park achieved early success in the field, but after Korea regained independence in 1945, she faced the challenge of eradicating all traces of the Japanese style from her work. Diverging from the tradition of conceptual works, she became determined to create a new type of Korean ink-wash painting in step with the contemporary times.

Continuously contemplating the Western modern art that flowed into Korea in the 1950s and the fundamental aesthetics of Korea, Park Rehyun never stopped pursuing new challenges and innovations. Even after reaching the pinnacle of the art world with two Presidential Awards in 1956, she continued to blaze her own trail as an independent artist.

II. Balancing Art and Life

Because of her domestic duties, Park Rehyun could never fully concentrate on producing artworks, which led her to question whether she could even call herself an artist. She carefully managed her schedule in order to spend as much time as possible in the studio, which she shared with her husband. She eagerly presented her works at “couple exhibitions” and exhibitions of the White Sun Group.

But even as Park steadily amassed fame and devotion, people continued to refer to her as “Kim Kichang's wife” or “the wife on the same path as her husband.” In reality, however, Park Rehyun refused to be confined in her husband's shadow, as she dauntlessly pursued new paths for Korean ink-wash painting by finding subjects, materials, and techniques in her daily life.

III. International Travel and Abstract Art

In 1960, Park Rehyun traveled abroad for the first time since her student days in Japan. While traveling through Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Japan, she witnessed the new international trends in abstract art, and thus dedicated herself to producing her own abstract works.

With this experience, she turned her eyes to the world stage. In 1964 and 1965, she and her husband presented their “couple exhibition” in three US cities, and immersed themselves in global art and culture while traveling through the US, Europe, and Africa. While visiting international museums, Park became enamored with the beauty of indigenous craftworks and ancient artifacts from various regions, which inspired her to reinterpret golden relics and traditional masks in new abstract paintings filled with curving yellow bands.

IV. Printmaking and New Techniques

After participating in the São Paulo Biennial in 1967, Park Rehyun traveled in Central and South America and the US. She then went to study tapestry and printmaking in New York, where she stayed until 1974. To expand her possibilities for expression, she spent years mastering the sophisticated methods of copperplate prints, one by one. After becoming proficient in each technique, she began presenting works that were free from technique.

After returning to Korea, she produced exceptional works that combined elements of printmaking and ink-wash painting. Sadly, her artistic journey was soon cut short by a sudden illness.

Make-up, 1943, Ink and color on paper, 131 × 154.7 cm, Private Collection

With this painting, Park Rehyun won the Governor-General Award at the 1943 Joseon Art Exhibition, while she was in her fourth year at the Women's School of Fine Arts in Tokyo. The viewer is immediately struck by the bold composition, with a girl in black facing a red mirror, isolated on a large pictorial plane with no background. Upon closer examination, the subtle details of the make-up brush and the girl's hands become apparent. Gazing at herself as she fixes her hair, the young girl has a confident expression and a firm kneeling posture. As such, the work seems to convey Park Rehyun's determination to begin her career as a painter.

Open Stalls, 1956, Ink and color on paper, 267 × 210 cm, MMCA Collection

With this work, Park Rehyun won the Presidential Award at the 1956 National Art Exhibition of Korea. Seeking to capture the everyday scenery from her visits to the market in the language of contemporary art, Park applied sharp brushstrokes of clear, light colors on a geometrically divided plane. This work showcases Park's keen sense of color combinations and her determination to reveal the beauty of daily life.

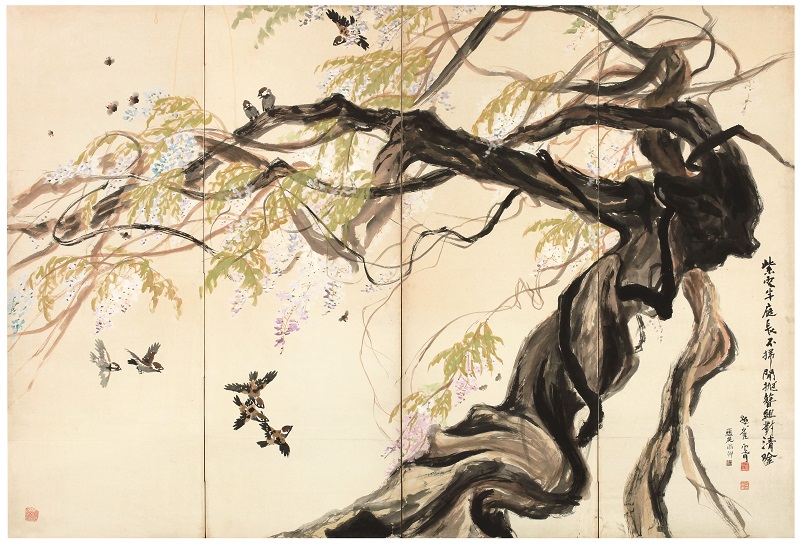

Park Rehyun, Kim Kichang, Spring C, c. 1956, Ink and light color on paper, 167 × 248 cm, ARARIO Collection

To create this collaborative painting, Park Rehyun painted the rattan tree, and then Kim Kichang added the sparrows and calligraphy. It was produced in 1956, the year that Park Rehyun received two Presidential Awards and assumed her place as one of Korea's leading painters. Her burgeoning confidence can be felt in the powerful brushstrokes that depict the aged trunk of the rattan tree.

Park Rehyun, “Marriage and Life,” Minseong, August 1948

“I wake up around six in the morning, wash diapers, prepare breakfast, and clean up. Then after breakfast, I tidy up around the house, look after the chickens, take care of my babies, and before I know it, it's noon. We eat lunch, and wile away a few hours if someone visits in the afternoon. Then after eating dinner, we might take a rest, but end up falling asleep from exhaustion. So when am I supposed to find the time to paint as my primary job?”

Park Rehyun, “Marriage and Life,” Minseong, August 1948

In the Forgotten History, 1963, Ink and color on paper, 150.5 × 135.5 cm, Private Collection

This is one of eleven works from the In the Forgotten History series that Park Rehyun showed at her 1963 “couple exhibition.” Rendered on traditional Korean paper, various circular shapes with permeating colors are connected by black lines, conveying an abstract representation of Korea's history. The following year, Park presented this work in the traveling “couple exhibition” in the US, under the new title Fantasy of Yellow.

Glory, 1966-67, Ink and color on paper, 134 × 168 cm, MMCA Collection

Representing Korea at the 1967 São Paulo Biennial, Park Rehyun showed this work, which was inspired by the indigenous cultures that she had learned about the previous year in American museums. Influenced by shamanist cultures and ancient myths, Park began producing new abstract paintings in three colors: yellow, symbolizing the sun; red, symbolizing human life; and black, symbolizing the historical era.

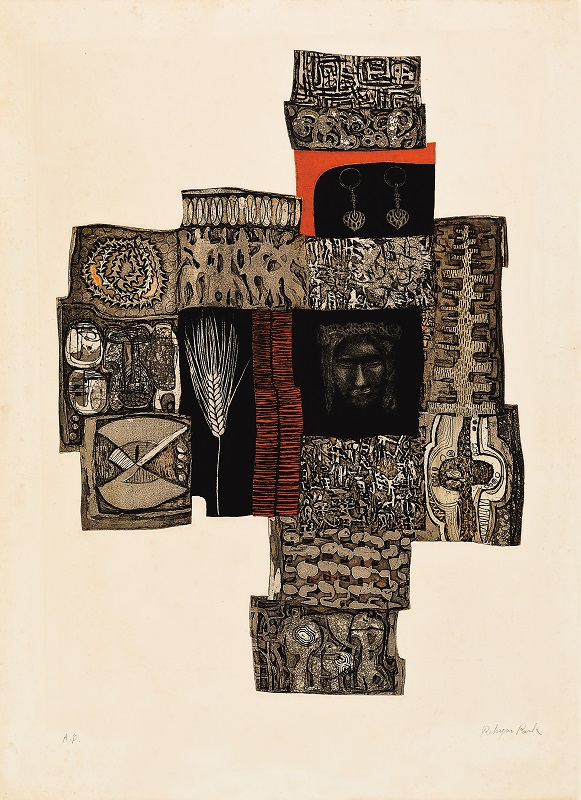

Recollection, 1970-73, Etching, aquatint, 60.8 × 44 cm, Private Collection

To symbolize history, life, and the earth, Park Rehyun combined many of her favorite motifs in this work, including traditional hahoe masks, Silla gold earrings, the womb, and grains. She cut copper plates into smaller pieces, engraved images on the pieces using various techniques, and then combined them on printmaking paper. The diverse, colorful images are unified by the red and black colors, yielding a narrative with a deep resonance.

Antiquity, 1975, Ink and color on paper, 66.5 × 59 cm, Private Collection

After returning from her study in the United States, Park Rehyun successfully presented Print Exhibition by Park Rehyun in 1974. She then embarked on an experimental series of ink-wash paintings adopting printmaking techniques—such as Antiquity—which she produced on her own printing press that she had brought from the US. For these works, she pasted thin traditional paper onto a backing of thick traditional paper, and applied numerous brushstrokes to create unique color tones that were moist but deep. Shown at the 1975 National Art Exhibition of Korea, where Park served as a judge, this work seems to declare the future direction of her work moving forward.